Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

Long Day’s Journey Into Night

By Michall Jeffers Long Day’s Journey Into Night is aptly named. At nearly four hours long, this glimpse into the life of a highly dysfunctional family can take its toll. The Tyrones are a mess. James, the patriarch (Gabriel Byrne), is a second rate actor who gave up dreams of playing great Shakespearean roles for a quick buck touring around the country in potboilers. His wife, Mary (Jessica Lange) is a morphine addict, and obviously has other psychological problems to boot. She fluctuates in mood and behavior from being the sweet, caring girl she remembers to being a shrill, bitter harpy who never lets her husband forget how he ruined her life. She repeatedly makes a point of saying that the shabby beach house they inhabit isn’t now and never was a proper home; and she’s always lonely.

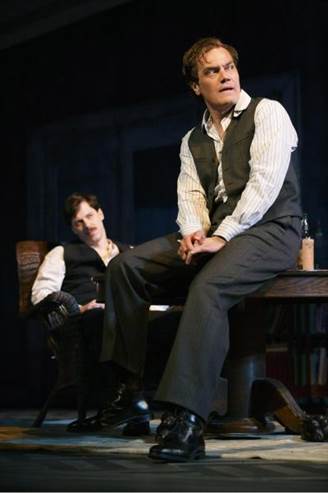

James Jr., known as Jamie (Michael Shannon) is a washed up never-was actor with a drinking problem. He loves his younger brother, but touts the life of dissipation he’s adopted. Consorting with whores takes the place of any real relationship that might have been possible with a woman. Edmund, the younger son (John Gallagher, Jr.) is confused and ill. He’s battling consumption, and is just as sick over the state of his family.

A large part of the problem is that James is terrified of poverty. In Ireland, his native country, being poor was a reality of life. Even though he’s comparatively well off, James still turns his back when he has to get money out of his wallet, and also employs the cheapest doctors he can find. If Edmund has to go to a sanitarium, Jamie pleads with his father to make it a good one, not just the least expensive to be had. He chides James for holding onto “the Irish peasant belief that consumption is always fatal,” so putting cash into a recovery is a waste of money. But James is 65, and no longer sure how much more of the itinerant life he can take; what then? Jamie is 34, and just barely hanging on to the semblance of a career, which was largely supplied to him by his father. They may all end up in the poor house yet. Investing in more possibly worthless land is the answer. It’s August, 1912, and everything is enveloped by fog, especially Mary as the day wears on. She claims she can’t sleep because of the foghorns, but every time she goes upstairs to take a nap, she comes down more vague than before. Everyone knows she’s shooting up, but she denies it. Jane Greenwood has skillfully dressed her in gray; Tom Pye has styled the Connecticut house in a white washed gray hue, too. Director Jonathan Kent has given the production a languid air, and even with expert performances by all the players, repetition and the downbeat vibe make the play drag.

Mary is ever concerned about her appearance; she was once the belle of the ball. She fidgets with her white hair, which is fixed in a progressively messier bun. She insists that Jamie has “a summer cold,” from which he will surely recover. Mary’s own father died of tuberculosis, and she can’t face the truth. The arthritis in her hands is acting up, and in pain, she rails against the fact that her husband was too cheap to even build the summer house correctly. Their dead son is always on her mind, and casts a further pall on the proceedings. He died of measles, caught from Jamie, who entered his room even though he was told not to do so. Mary holds onto the notion that Jamie intentionally wanted to hurt his brother. If there were ever any doubt that this is an semi-autobiographical hard look into O’Neill’s own family, the playwright has named the son who died “Eugene.” It seems like a reference to the death of his spirit living in a house of psychological torture. The play was written in the early 1940’s, but locked in a vault and not performed publically until 1956. Considered by many to be his best work and a classic of the American theater, it won both the Tony for Best Play, and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Edmund Tyrone expresses his wish to someday become a great writer. Harker, a neighbor frenemy of James, known as "the Standard Oil millionaire", is thought to be based on Edward Harkness, heir to Standard Oil, who also had a summer house in Connecticut. The O’Neill’s summer home in New London was called “Monte Cristo Cottage,” named for the melodrama James O’Neill performed over 6,000 times. In the play, James mentions he once worked with renowned actor Edwin Booth; this is a fact. “Tyrone” is the name of the earldom granted to an O’Neill ancestor. The ages of the family members are the same as the O’Neill’s in 1912; Eugene was 23. Mary O’Neill was a good Catholic girl who went to a convent school. As foreshadowed in the play, Jamie did die of alcoholism in 1923. Like Edmund, Eugene had been to sea, and did suffer from TB and lived in a sanatorium in 1912-13. Thus, 1912 was a pivotal year in the young author’s life; when released back into the world, he threw himself into his work, and was motivated to become successful. Long Day’s Journey Into

Night is not a fun

evening at the theater, but with the masterful performances of the company, as

led by the luminous Jessica Lange and the soulful Gabriel Byrne, it is well

worth taking the trip to a beach house surrounded by fog and full of dreams set

adrift. |