Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

Phalaris' Bull : Solving the Riddle of the Great Big World

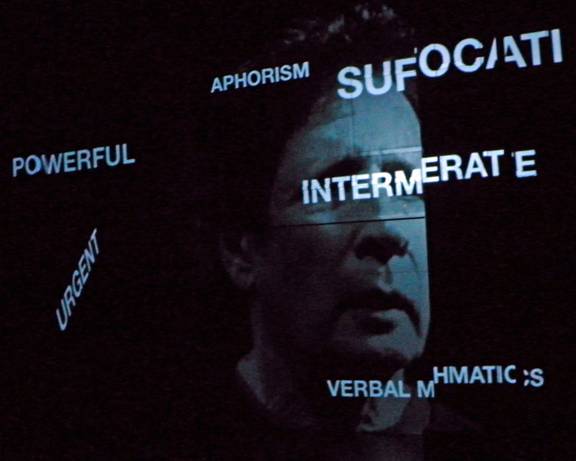

Steven Friedman Photos by Gerald Slota

Phalaris’s Bull: Solving the Riddle of the Great Big World

by Julia Polinsky

Enchanting or annoying: which? You’ll have to make that decision for yourself. Steven Friedman’s Phalaris’s Bull claims to be “solving the riddle of the great big world.” In the process of trying to understand what he’s saying, that may, or may not happen. And you may, or may not, stay awake through the 80 nonstop minutes of his dazzling tour de talk.

I say “understand what he’s saying,” because this one-man show is basically a philosophy lecture on steroids, handsomely mounted in a dynamite, deeply semiotically informed set by Caleb Wertenbaker. With projections by Driscoll Otto and lighting by Jimmy Lawlor, the show is intriguing and engaging to look at, playing with the concept of opening and closing doors and windows and looking through them into the ideas behind.

Director David Schweizer has done what he can with a singular challenge: how to shape the work of a hyperactive, super-intellectual, hubristic polymath, let him do his thing on stage, and make it entertaining? Face it: when was the last time you went to the theater and heard the words “heuristic” and “epistemic,” or had Kierkegaard, Wittgenstein, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Hume, and the Buddha thrown at you?

Not everybody’s cup of tea, that kind of thinky-thinky talk. If you don’t want to stretch your mind, then Phalaris’s Bull is not for you. If you do, it can be deeply rewarding, provoking lots of thought.

Friedman, the author of the piece, and a writer, poet, and visual artist, uses the word “genius” in reference to himself – although always, he credits someone else with describing him that way. Maybe yes, maybe no. Friedman may have many, many talents and skills, but acting is not among their number, unless you count “being himself” as acting. Natural, and comfortable speaking to a group, but not an actor. It would be interesting to see someone do the show who had not lived the story – that would be an acting challenge, indeed.

At the opening, he comes out on stage, invokes Kierkegaard, and describes the story of Phalaris’s Bull, an ancient torture device. The Bull was a hollow, bronze statue, in which the victim was placed, and then roasted alive; it was designed so that the viewers/audience heard the screams from within as music.

Hard to believe. Screams as music? Look it up. Lucian, the historian of that time and place, writes this description:

The tyrant need only place his victims inside the hollow statue, place auloi (reed instruments from ancient Greece that were associated with the cult of Dionysus and therefore tended to be used in music that was orgiastic or emotionally overwrought) in the nostrils of the bull, and place the bull above a raging fire. As the bronze heated and burned the trapped victims, their screams would be transformed into “the sweetest possible music by the auloi, piping dolefully and lowing piteously” (see Lucian, Lucian, vol. 1, trans. A.M. Harmon. NY: Macmillan, 1913, pp. 17-19).

Also, the bull was a gift from Phalaris to the oracle at Delphi, as a sacrifice to Apollo. So, from the get-go, Friedman practices poetic/dramatic license, leaving out the inconvenient details – the religious significance, the auloi -- that give the title, and the impetus for the show, their power; without auloi, it simply makes no sense that the sound of screams in bronze is music. Without Apollo, the Bull loses a layer of importance.

Lack of detail: it’s the start of a pattern that occurs throughout the show. Oh, Friedman includes information about his life, his school years, his romance, his wife, his family, his art, his studies, how many teachers or rabbis or mentors have called him a genius. Those details, he shares. But the nuts and bolts of his philosophy? Not so much.

He also starts the evening with the philosophy lecturer’s equivalent of a cheap trick, then goes on to use the frame of that trick to hang his lecture –oops, show – together. You may find such tricks enchanting. You may not.

How does the saying go? If you can’t convince with logic, baffle with bullshit? Friedman states, over and over, that philosophy solves the riddle of the great big world; that art, poetry, science, belief, and faith, are not enough to “…address the extremity of human suffering.” Only philosophy, with what he claims is its rigor, can Fix Everything.

Oh, yes. Friedman has the answer, and he tells us how to get back to Eden. To a world in which there is no suffering. You may want to see his performance, to find out what that is. If you do, do yourself a favor and buy the script, available as you exit. Reading, and re-reading it, can be very rewarding.

Phalaris’s Bull: Solving the Riddle of the Great Big World At the Beckett, on Theatre Row 410 W 42nd St, between 9th-10th Through January 16 http://solvingtheriddleplay.com Tickets: http://solvingtheriddleplay.com/#tickets

|