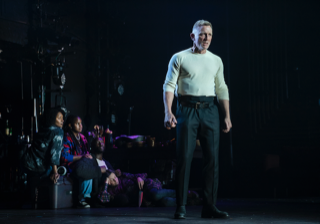

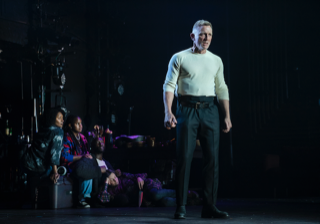

Daniel

Craig, Ruth Negga, as Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, in Sam Gold’s Macbeth

Photo: Joan Marcus

Macbeth

A Review by Deirdre Donovan

In a stop-and-go season, when so many productions were put on pause for

COVID-forced absences, the new staging of Macbeth, helmed by

Sam Gold (Fun Home), at the Longacre Theatre holds the

brave distinction of closing out the 2021-2022 Broadway season.

First, the good news. Gold’s mounting of the Scottish play has

two mega-voltage stars, Daniel Craig and Ruth Negga, leading the cast

as the diabolical Macbeths. What’s more, Craig and Negga have

that elusive thing called “good chemistry” from the

get-go. Indeed, when Negga’s Lady Macbeth leaps into her

stage husband’s arms and seductively entwines herself around his torso

in Act 1, the temperature in the theatre truly ratchets

up. And it also gives fresh definition to the late

Shakespearean scholar Harold Bloom’s characterization of the Macbeths

as the “happiest marriage in Shakespeare.”

Another boon to this revival is how it investigates the stage

superstitions surrounding Macbeth. In a curtain speech,

presented by the terrific Michael Patrick Thornton, (he performs Lennox

and an assassin in the play proper), we are given a mini-history

on Macbeth and how the historical King James I (he first

was James VI of Scotland before succeeding Queen Elizabeth in 1603)

almost certainly influenced the witch motif in the Scottish Play. The scholarly

king was obsessed with witchcraft and wrote a book

entitled Daemonologie (1597).

Thornton continued his yarn by sharing that the prolific Shakespeare

wrote Macbeth, King Lear, and Antony and Cleopatra, in

quarantine, circa 1605, when the public theaters were closed during the

plague. Thornton then paused, looked the audience in

their collective eye, and pointedly asked what they had done of note

since the pandemic arrived in our midst two years ago. The

silence that followed was palpable.

Thornton wrapped up his curtain speech by mischievously asking viewers to

forget the cultural taboo about Macbeth and to say the

play’s name silently under their masks to the person sitting next to

them. No question this staging of Macbeth is

intentionally meant to rattle the stage superstitions haunting this drama.

Witches are writ large in Gold’s production. Indeed, even

before the play proper begins, we see the witches in modern-dress

(costumes by Suttirat Lalarb) cooking up who-knows-what in a kitchen on

a mostly bare stage (minimalist set design by Christine

Jones). And, in contrast to the more conventional witches in

other revivals of Macbeth, these Weird Sisters look like they are

having one helluva time creating their brew.

Don’t forget to read dramaturgs Michael Sexton and Ayanna Thompson’s

program note. They persuasively argue that

the production’s sparse scenery and actors performing multiple parts

mirrors the theatrical practices of the early

17th century. Or as they aptly put it: “This

production, like the theater of Shakespeare’s time, is one of minimal

scenery and maximum fluidity and speed. There are no

major scene changes, and the actors play multiple roles. This

simplicity and flexibility, in which the play’s language carries most

of the narrative and expressive weight, enables a high level of

imaginative participation.”

Whether you buy into their argument or not, Sexton and Thompson do provide

some fascinating historical information on the stage practices of

Shakespeare’s time and how Gold’s production, more or less, dovetails

with it.

Now for the not-so-good news. Gold’s innovative touches in

his production, as brilliant as they may be, don’t make his

modern-dress Macbeth all that accessible to many

theatergoers. Take his minimalist staging and fluidity of

role-playing, which has many actors in his 14-member cast doing double or

triple duty in the show. Even those who are familiar with the

story of Macbeth might find themselves playing Sherlock Holmes

as Maria Dizzia’s Witch morphs into Lady Macduff and then

a Doctor. Indeed, it is difficult at times to know

what character we are looking at in this briskly-paced production.

Of course, there was no problem in identifying the titular character

Macbeth, as performed by the James Bond actor Craig, or Lady Macbeth,

as impersonated by the exotic-looking Ruth Negga. Asia

Kate Dillon, with her purple coif, is quite easily identified as the

royal Malcolm and future king. And, in spite of his triple duty as

King Duncan, the Porter, and Siward, Paul Lazar somehow manages to

delineate his roles with crystal-clear outlines.

Macbeth is the best known of Shakespeare’s

plays. And it would be tedious to recount its plot details

here. But, suffice it to say, that Macbeth is a story of

an overly-ambitious Scottish general who gained the world and lost

his soul.

Daniel

Craig, as the titular character, in Macbeth

Photo: Joan Marcus

Kudos to both Craig and Negga for tackling the plum Shakespearean roles of

Macbeth and the Queen with brio. Although

Craig doesn’t quite capture the vulnerability of the conscience-stricken

Macbeth in the first several acts, he has no problem impersonating

the Thane as “Bellona’s Bridegroom” or Lady Macbeth’s torrid

lover. Craig, with his muscular physique and steely demeanor surely

looks the part of Macbeth. And his performance is at

its best when his character is fighting against impossible odds (think

of the moving grove that comes to Dunsinane in Act 5).

Ruth Negga, playing opposite him, however, is the real star

turn. Her emotional immediacy and natural phrasing of the

verse makes one readily understand what she’s spoken--and left

unspoken. She has acting range too, capable of first projecting

herself as the impervious Lady Macbeth, and later on, as the

light-obsessed Queen who sleep walks at night, trying to wash her hands

clean of Duncan’s murder.

Ruth Negga,

as Lady Macbeth, in Macbeth

Photo: Joan Marcus

Don’t expect to hear the familiar witches chant: “Double, double toil

and trouble; Fire burn and cauldron bubble” in this

production. In fact, a lot has been jettisoned from Gold’s

retooled version of Macbeth. It’s almost as if Gold is

attempting to pare the tragedy down to its bone, in hopes of discovering

its essence.

This Macbeth becomes the fourth major Shakespeare production staged

by Gold. His Othello with Craig and David

Oyelowo

at the New York Theatre Workshop was a hit with the critics and

public alike. His irreverent but likable Hamlet at

the Public Theatre with Oscar Isaac at the Public

Theatre was also a crowd-pleaser. Less popular was

his King Lear on Broadway, over-spritzed with Philip Glass’

music, though almost redeemed by the great actress Glenda Jackson playing

Lear.

Returning to the current production, what does the invented “soup scene”

mean at play’s end, in which the company gathers on stage for a hearty

communal meal of soup? Indeed, the scene is likely to

satisfy some, and puzzle others. Although

it’s impossible to know precisely what Gold is up to here, one

can certainly speculate on the scene’s meaning, whether taken at its

face value (soup is famous for nursing folks back to health) or as

symbolism that a stronger community is on the horizon.

But how did Gold come up with a soup motif for his invented

epilogue? Is the company acting as a chorus and perhaps

pondering Macbeth’s haunting words from Act 5, “I have supped full of

horrors.”? Or are they simply presenting themselves

as survivors of the tyrant Macbeth? Or does the scene

bleed into real life and make us think of the tyrannous COVID-19

virus that has killed so many of our loved ones in the past two years

and severely disrupted our lives?

In any event, Gold is not the first artist to retool a Shakespeare play

with a coda. After all, didn’t theatrical companies

in Shakespeare’s time dance a “transitional” jig at play’s end, a signal

to the actors and audience alike that it was time to leave the

fictive world and return to the real world of responsibility?

Okay, Gold leaves the audience with more questions than answers with

his Macbeth. But, fortunately, the vastness of

Shakespeare allows for many interpretations of the

tragedy. Gold, in his new provocative production, might

not please all theatergoers. But he surely gives one a fresh point

of departure to reconsider the truths at the core of this bloody

tragedy of ambition.

Through July 10th.

At the Longacre Theatre

220 W. 48th St., Midtown West

For tickets, phone 212-541-8457.

Running time: 2 hours; 20 minutes with one intermission.

![]()