Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

In White America

by R. Pikser In the early 1960s Martin Duberman culled historical records of both Blacks and whites. With this information, he wrote a play about the Black experience in the United States: In White America. His selection of materials and how he arranged them, made those records live. It must have been gratifying, or shocking to many to see on the stage what had been only passed down within families, or what had been locked away in legal documents, or what had been locked in the deepest recesses where we hide our pain, or our guilt. In this 50th anniversary presentation, produced by The New Federal Theater and the Castillo Theater, many of these excerpts, though not seen for the first time, still are shocking, not the least so because they are still relevant. The relevance is the more painful because we are in a period when the fragility of Black lives has once again come into national (white) consciousness.

The first half of the play starts with the capture of Africans, their deaths on board the transport ship where they were packed on their sides, like sardines, and their torture and/or rape while in control of the whites, as documented in his journal by a shipboard doctor. It moves through thoughts and reactions of the enslaved; speeches by Quakers against slavery; an excerpt from Thomas Jefferson showing his best side, not the side in which speaks against the humanity of his slaves.

Nalina Mann. Photo by Gerry Goodstein.

There are speeches by whites denigrating the slaves and even letters between former slaves and their former masters, the slaves showing quite a bit of humor along with the justice of their claims and the masters clearly not able to understand how their former property could be so contrary and unkind to them as to not wish to return. We hear Sojourner Truth and John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and one of the white northern commanders of the regiments of Black troops who is awed by their determination and their ability to sacrifice. The Civil War marks the intermission of the play.

L-R: Shane Taylor, JoAnna Rhinehart, Art McFarland. Photo by Gerry Goodstein.

After the war, we hear from a Klansman, boasting of how he whipped and lynched Blacks. We then hear from a woman tortured by the Klan: for having purchased her own house, for refusing to have sex with the whites, for standing up to the whites. There are the voices of Booker T. Washington, and his nemesis W. E. B. DuBois. We hear Marcus Garvey and from Father Divine and one of his devotees, and from an illiterate sharecropper forced to do gang labor like a convict for the debt he has incurred at his boss’ company store. We even hear Paul Robeson speaking with utmost dignity before the hectoring of the House Un-American Activities Committee. And we hear the story of Little Rock High student Elizabeth Eckford who took the bus to school, alone, on the first day of school, and was nearly lynched. The play is a treasure trove of documents. Though reportorial in structure, there is much passion in and beneath the words, even the most measured words of the public officials. If that passion and intensity are not made present, this country will never understand how intractable the problems of racism are. These are matters that touch the deepest part of each of us. That is why the performances were often disappointing: The passion, or its subtext, was too often missing, as was the homework necessary to flesh these people out. The danger in actors performing many characters in one play is that the actors may fall back on a series of impressions, rather than creating a history and a subtext for each character; This was often the case in this production.

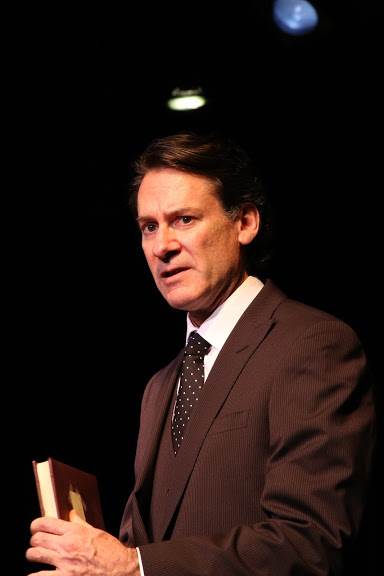

Bill Tatum

Musician Bill Toles. Photo by Gerry Goodstein.

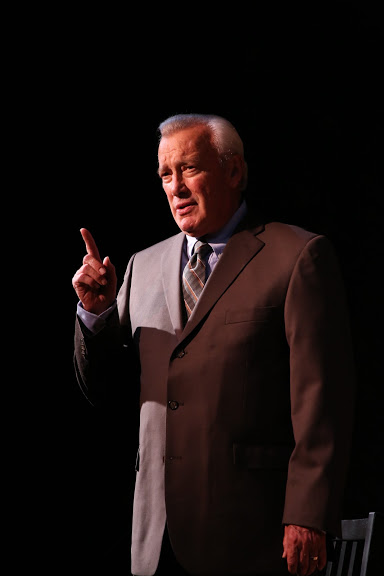

Charles Maryam has staged the play simply, with one musician (guitarist, percussionist, and vocalist) upstage left on a riser, six actors, three African American, three white, two men and one woman of each, on stools and chairs on somewhat lower risers, with one simple table downstage center to serve as desk or podium or whatever else is needed. The deceptively simple lighting, always clarifying, was designed by the famed Shirley Prendergast, and Gail Cooper-Hecht’s costumes were attractive, yet unobtrusive, providing unity to the ensemble.

The New Federal Theatre is asking the public to request more State support for itself and for the other members of the Coalitions of Theaters of Color. Their work is still necessary. It provides us with a part of our culture, whether we are Black or white, that otherwise we do not see.

In White America October 15th–November 15th 2015 Castillo Theater 543 West 42nd Street New York, NY 10036 Tickets $40 $30 students and seniors If ordered from ovationTix 866-811-4111, add $3 www.Castillo.org/www.newfederaltheatere.com 212 353 1176/newfederal@aol.com |