Editor : Jeannie Lieberman |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us | ![]()

For Email Marketing you can trust

The Iceman Cometh

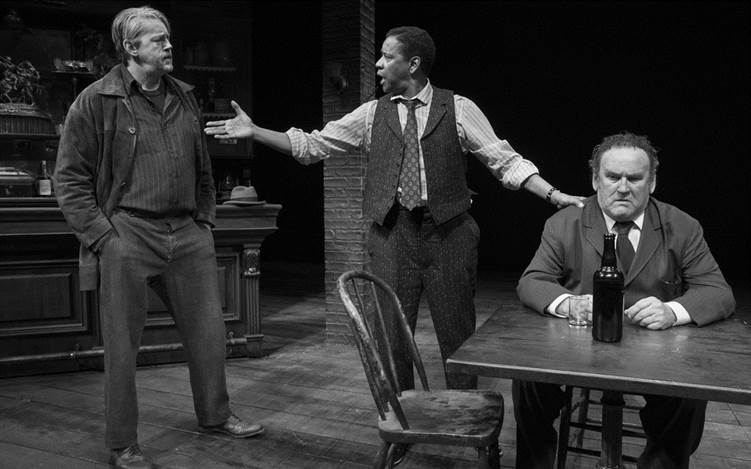

Denzel Washington and the Company of ‘The Iceman Cometh’ PHOTO: JULIETA CERVANTES

By Ron Cohen

You wouldn’t want to stay overnight at Harry Hope’s Saloon and flophouse in Greenwich Village, circa 1912. It’s a place inhabited by down-and-outers, has-beens and never-beens. But for nearly four hours, these folks as portrayed in this George C. Wolfe-directed revival of Eugene O’Neill’s classic treatise on despair and illusion, The Iceman Cometh, prove to be as vivid and surprisingly entertaining a group of humans as you are likely to find on a Broadway stage this season.

The centerpiece of the production is, of course, the presence of Denzel Washington, as the effervescent hardware salesman Theodore Hickman, known as Hickey, whose semi-annual party-throwing visits to Harry Hope’s are manna to the hostelry’s grim denizens. His largesse means free drinks, food and great stories, such as the jokes he cracks about leaving his wife in the care of the iceman.

Washington, in his fifth Broadway appearance in 30 years, proves once again to be as dynamic a performer on stage as he is on screen, perhaps even more so. And in this production, a similar dynamism is apparent throughout the cast. The 19-person company is simply chockablock with terrific performances.

Furthermore, director Wolfe explores every possibility for humor in O’Neill’s obsessively dark writing, and his actors respond brilliantly. The laughs come from language, personality and situation, even as the characters wallow in their alcohol besotted lives. You’re probably not going to split a gut from laughter, but you may be surprised at how often you smile, chuckle or chortle, as the comedy brightens a crowded palette of thoughts on politics, gender and racism, as reflected through the prism of mid-20th Century America. O’Neill wrote the play in 1939, but it did not premiere on Broadway until 1946. Since then, it has been frequently revived, with the role of Hickey attracting such actors as Jason Robards, James Earl Jones, Lee Marvin (in a filmed version), Nathan Lane, Brian Dennehy and Kevin Spacey.

In this production, Wolfe’s direction also crackles with urgency, infusing the story-telling with suspense (even if you know the outcome), as Hickey’s visit this time around – on the occasion of Harry Hope’s 70th birthday -- takes on an unexpectedly ominous tone. Hickey announces right off that he has stopped drinking and then that he has come with a new mission, to rid the inhabitants of their “pipe dreams,” the false illusions that both sustain and haunt them. He promises that they will find peace in the process, just as he has. It’s not a situation that goes well, and Hickey’s epic monologue as to what has happened to him is the play’s searing climax. It’s delivered by Washington in mesmerizing fashion, sitting himself downstage, talking directly to the audience for more than a quarter-hour or so.

David-Morse, Denzel Washington, and-Colm Meaney in THE ICEMAN COMETH. PHOTO: JULIETA CERVANTES

But as impressive as Washington’s Hickey is, the production is crowded with a gallery of portraits that are equally enthralling. They include Colm Meany as the proprietor Harry Hope himself, a one-time ward heeler who has not ventured outside his establishment since his wife’s death twenty years earlier; Bill Irwin as Ed Mosher, Hope’s brother-in-law who used to work for the circus and now spends his time figuring out how to snag one more free drink, and Jack McGee as Pat McGloin, their long-time pal, once a cop before his corruption caught up with him.

Frank Wood and Dakin Matthews portray a couple of former military men who fought on opposite sides of the Boer War and continue to do so in their intoxicated, often quite funny belligerence. Reg Rogers plays a journalist who covered that war and dreams of going back tomorrow to a job no longer his, thus earning him the moniker of Jimmy Tomorrow.

Neal Huff is a spectral figure as Willie Oban, bemoaning the fact that he’s a Harvard Law School graduate, destroyed by the law-breaking of his businessman father. Michael Potts embodies Joe Mott, who once owned a gambling house and now explosively ponders drinking and his life as a black man, and Clark Middleton’s Hugo Kalmar is an ancient revolutionary, who occasionally awakes from a drunken slumber to bark out exclamations.

Carolyn Braver and Nina Grollman portray two hookers (they prefer the term “tarts”), who live at Harry Hope’s, paying a portion of their earnings to the gruff bartender, Rocky (who refuses to be called a pimp), played by Danny McCarthy. Tammy Blanchard is Cora, a third prostitute whose “pipe dream” is her plan to marry Chuck Morello, another bartender, played by Danny Mastrogiorgio, and move to a farm in New Jersey.

Finally and probably most importantly, there’s David Morse’s Larry Slade, a one-time anarchist. Slade is a man of deep disillusion with “the movement,” claiming to be awaiting only the peace of death. Slade’s cynical armor is cracked by the appearance at Hope’s of young Don Parritt, played by Austin Butler, the confused and frightened son of Slade’s one-time girlfriend, still an avid anarchist and now jailed for a bombing in San Francisco. It is with these two figures that Hickey feels the greatest connection, a connection which they resist.

It’s a rich, crazy quilt of a dramatis personae, but the actors and the production keep them all indelibly defined. Ann Roth’s costumes help in that regard, while Santo Loquasto’s set and the lighting by Jules Fisher and Peggy Eisenhauer heighten the atmosphere giving us three different views of Hope’s saloon.

The only off-note in Wolfe’s direction would be the rather limp endings he gives to the first three of play’s four acts. It almost seems as if his intention is to muffle interim applause and not distract from the devastating final curtain.

This is a minor questioning, however, of a production that is monumental theater, a production that offers a stage packed to the wings with reasons to revisit this tragic assessment of the human condition.

Broadway play Playing at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre 242 West 45th Street 212-239-6200 Telecharge.com Playing until July 1 |